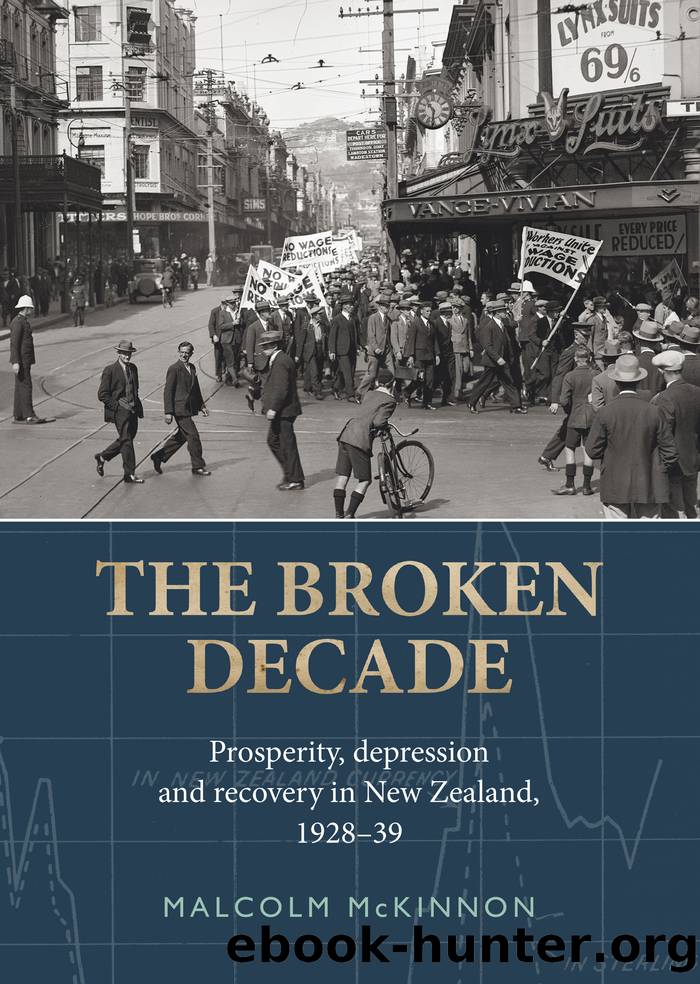

The Broken Decade by Malcolm McKinnon

Author:Malcolm McKinnon

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Otago University Press

Published: 2016-07-15T00:00:00+00:00

Cover of the Official Report of New Zealand’s Hunger Marchers. P Box 303.61 JEN 1934, ATL, Wellington

At the opening of the restored Waitangi Treaty House, 6 February 1934, the day after the Gisborne marchers reached Wellington.

Frank Douglas Mill, FMO-00029-G, F. Douglas Mill Collection, Auckland Libraries

The failures were not owing to lack of zeal or of collaboration. Although a number of Communist Party leaders had been imprisoned in mid-1933, the return of Fred Freeman to an active role in the latter part of 1933 revitalised the party and the UWM.44 In Auckland one task was to ‘win over individual members and whole branches from the APUWA’ (Auckland Provincial Unemployed Workers’ Association) and its most vigorous invective was directed at F.E. Lark, the APUWA leader and president of the Labour Party-affiliated National Union of the Unemployed (NUU). The paper reported that at one meeting ‘a couple of Lark’s thugs tried to provoke a heckling comrade by asking him to “come around the corner”’, and that ultimately Lark left in the company of a policeman, snarling, ‘How will you justify your actions to [UWM leader] Jim Edwards when he comes out?’45

The newly established Communist paper, the Workers’ Weekly, had reported disparagingly Lark’s comment that ‘now if ever is the time for us to have businessmen, the churches and every section of the community in this struggle of the oppressed relief workers’.46 In Gisborne precisely such alliances were formed. Was protest then a waste of time? Events through the winter of 1934 suggested no, but that protest needed to take place in main, rather than secondary, centres, to be successful.47

For fortuitous reasons, events in one secondary centre – Palmerston North – probably did have an impact on policy.48 Through 1933–34 the number of registered unemployed in that town was consistently over 1000, as it was in Whanganui but in no other secondary centres.49 The prospect of 50 married men being required to go to a camp on the bleak Kaingaroa Plains was one trigger for the demonstration on 22 May 1934. ‘With banners flying,’ according to the Evening Post, a crowd marched to the main entrance of the Masonic Hotel and demanded to see Forbes, who was in the town at the time. ‘We ask,’ said Councillor Joseph Hodgens, a Labour Party member, ‘for the prime minister, as a family man, to consider the predicament we are placed in and that our men are being driven into a slave camp on the Kaingaroa Plains.’50

When the prime minister finally spoke, from a balcony, the crowd was hostile and vociferous, a mood that had built up as time had passed while they waited for him to finish his dinner. ‘Deafening cheers’ as Hodgens spoke gave way to ‘boos and hisses’ once Forbes started. One person present recalled that the authorities wanted

to create a riot scene there, with soldiers in the background and machine guns and whatnot. Some of the spectators threw tomatoes and eggs and that, but this was uncalled for by the unemployed because we didn’t believe in any unnecessary provocation.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32554)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31951)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31935)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19067)

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(14376)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13324)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12022)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5368)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5217)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5093)

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow by Yuval Noah Harari(4911)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(4775)

Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl(4591)

The Silk Roads by Peter Frankopan(4528)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4474)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4209)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4107)

The Motorcycle Diaries by Ernesto Che Guevara(4094)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3963)